FOREST PRIMEVAL

a secret history of what resides in the last remaining old growth forest in Eastern Europe

text from completed novella, drawings from inktober 2017

They say I was my sister’s shadow. I was dark and I followed her. Not only was my hair dark—fine, black hairs trailed my arms and shins like the spring pelt of a shy beast and shadowed the distance between my eyebrows—but my demeanor was also dark. You know this word? Demeanor? It means I was mean. Ungenerous. I didn’t see the good in people, but maybe they never showed it to me.

What has been recorded as the history of civilization—as a hand print on a cave wall, as runes scratched in stone, as tallies on clay pots, as drawings on papyrus scrolls, as wing-feathers dipped in ink, as metal pressed to paper—all these have proven to be less substantial than the stories written in the rings.

It was no accident their papers were made from wood pulp, and no surprise when humankind started writing their histories on the wind. The fleeting, ever-fading moments of an individual’s life. The slow realization that what was once will never be again, and what is now is sure to end. Even at this moment in the story, the listener is fading, blurring around the edges, becoming something other in the telling. It is why.

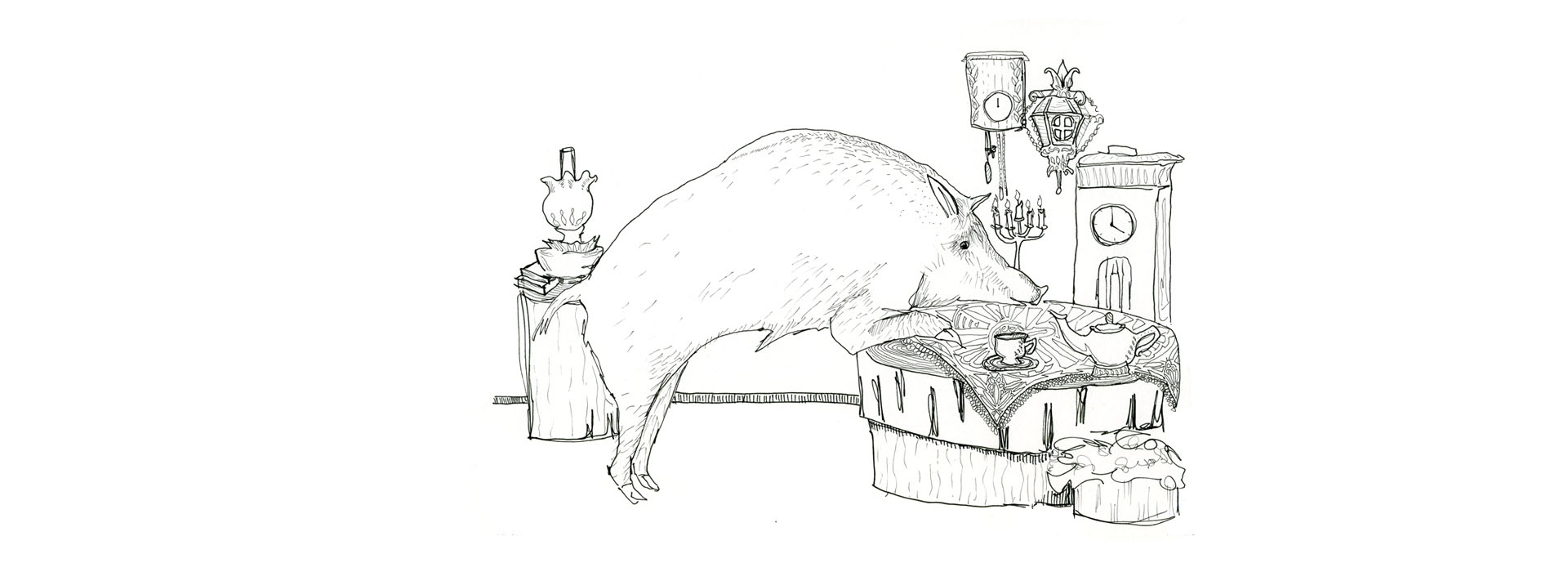

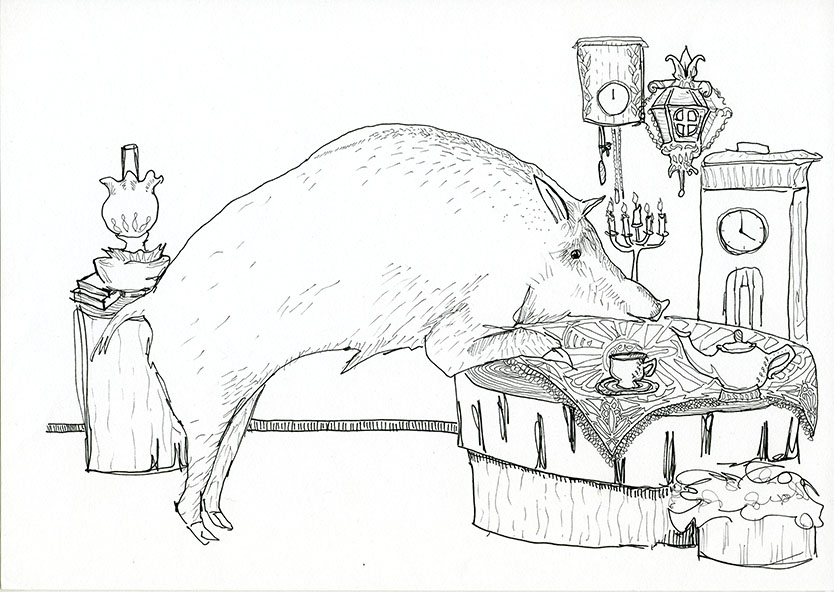

We entered the cottage, which felt larger on the inside, despite being cluttered with aristocratic keepsakes and crowded with creatures one often does not find indoors. There was a peacock perched on a hat rack. A black stork nested in a travel trunk. A young lynx looked up lazily from the bed, the black tip of its stub of a tail twitched. Two twin moose calves poked their necks in through the kitchen window and stole some sugar.

Natalya clutched my hand as a nine-hundredweight boar lifted its head off the sofa and moved to inspect us.

The large animal nudged her wet snout against my hand, the coarse hair brushing firm against my arm. She was immense. Her tiny bleary eyes ignored us as her nose investigated everything. “Isn’t she too big to be inside?”

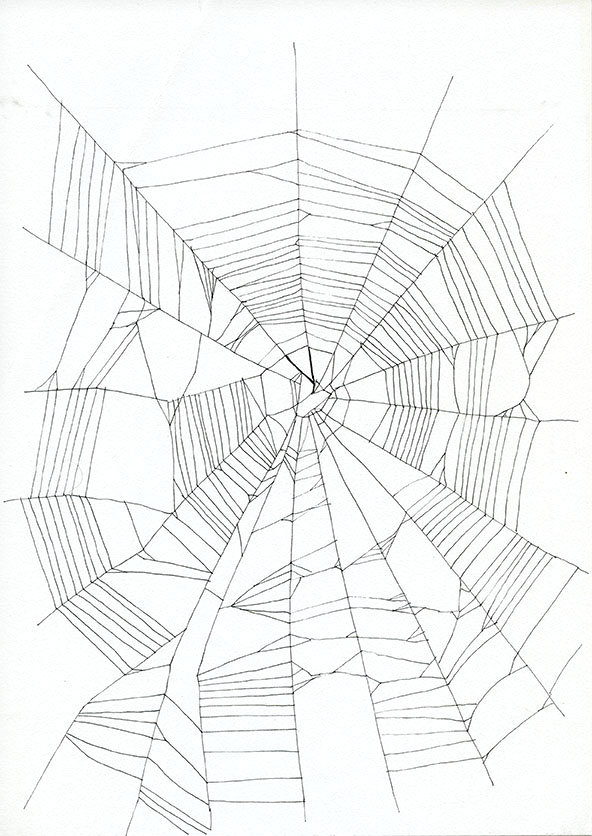

There once was an old woman alone in the wood who sat beneath the bough of a whispering tree. She sat with her spinning wheel always spinning and the whoosh of its winds moved the clouds in the skies. She gathered spider’s silk and spun it into spools, and from those spools she wove the forever fabric.

The fabric was endless and covered the wood and it covered outside the wood, the sea and the stars. And all the things it covered were reflected in the pattern of the infinite designs. The old woman sighed and enjoyed the work and the company of the whispering tree.

Now, the dark woods were enchanted, as everyone knows. Cursed and enchanted, both darkness and light. Strung around the core of the ancient woodlands, was a curse protecting it. It was the same curse that inspired the riddle, How far can you walk into the forest? Answer: Half-way, then you are walking out of it.

But there is a center to the dark woods, though travelers never find it. A single strand of spider web, fortified by a whisper, was usually enough to deflect wanderers away from the forest core. To keep trespassers out. However, this young traveler moving through the darkness, following the light, passed right through the cursed boundary.

The sorceress who cast the curse felt the silk string snap, heard the truths fly through the darkness like dewdrops released. She cried, “Look how she travels right through my curse! Why hasn’t the despair brought her to her knees?” The traveler responded, to the voice inside herself, “I have no hope of ever getting though this wood. Why should I feel the curse, when I have been cursed all my life?”

The folk watched the sleeping child with more excitement than apprehension.

A human child! It had been so long.

Though not long enough for some.

She was not a lovely child. Her skin was pale and her hair dark, though nothing like Little Snow White’s. “Good for her,” one of the dwarves remarked. “One less jealous queen to hunt her down.”

“The red-cap though? The red-cap!” The goat’s square pupils wild in her bulging eyes. “What do you make of that?”

Rumpelstiltskin picked at the child’s shawl as if assessing its quality between his imp fingertips. “It’s a so very dull red, though,” he muttered. “Hardly even a color. More a shade.”

“You’re always looking for coincidences, you old goat,” a small bear chastised. “A reason to get worked up that there might be wolves about.”

What’s your favorite story?” a mouse asked.

Dasha chewed another nut slowly. She knew her answer to this question would have to be very diplomatic to not hurt anyone’s feelings. The answer, she felt, might have the power to influence the Storyteller, if that was at all possible. She swallowed. “I like the stories where both the sisters live happily ever after.”

The folk grew silent around the table, their brows furrowed. Then they started muttering, consulting with each other. “I don’t think I’ve ever heard that story, have you?”

“How does the story go?” the mouse inquired.

Dasha opened her mouth to begin the tale of two sisters, their harrowing tale, and happy ending, but no words came out. The Storyteller wouldn’t allow her to tell her own story. “It would be a new story,” Dasha finally said. “One no one has ever told before.”

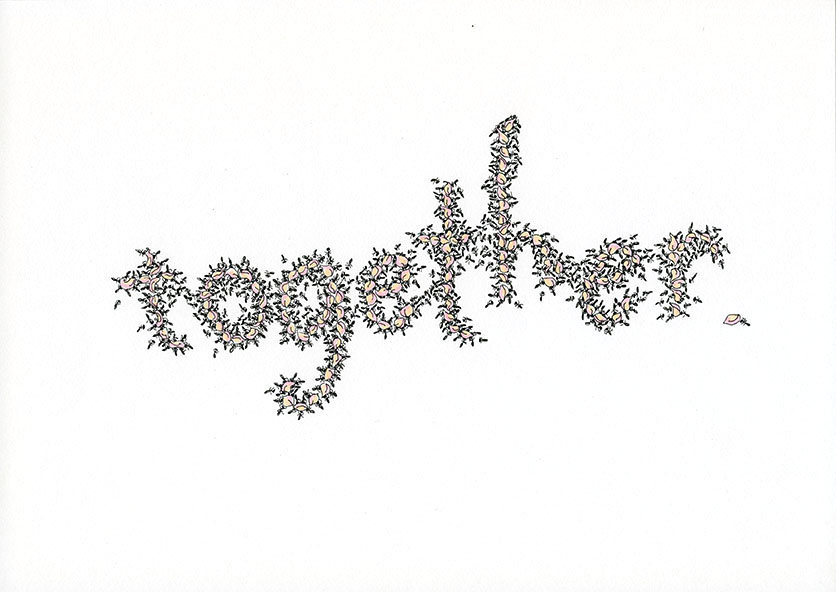

Dasha looked down to see an entire string of ants pausing on a fallen log, all turned to her, watching. “Don’t you have something better to do?” she asked them. One started tugging on a pink petal, while the others still watched her. Then they joined in the activity.

A pattern formed on the dark leaf litter, the pink petals arranged to spell nope.

Dasha was enthralled with the ants’ astounding accomplishment. “You can write?” she exclaimed. “How did you do that?”

The ants crowded and huddled and tripped over each other. Some of the petals taking the long way around to get back to near starting position to spell out the word together.

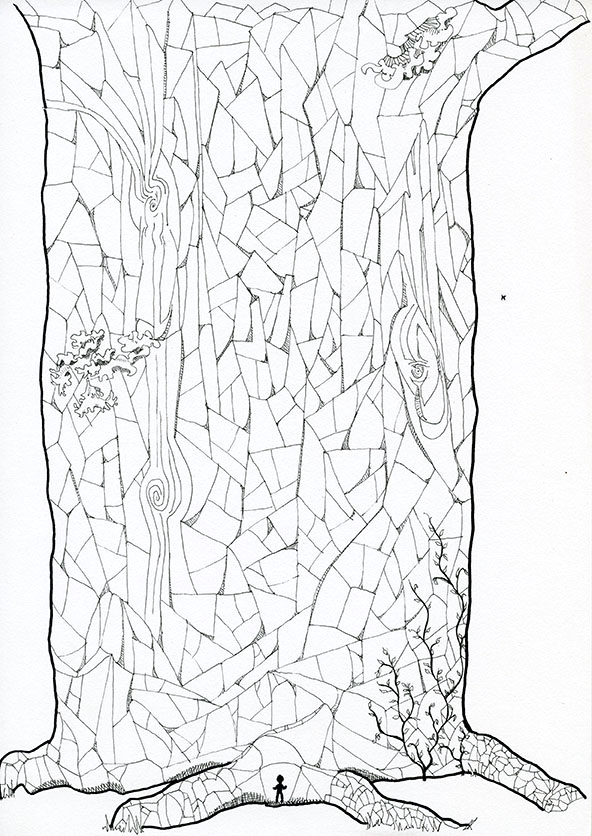

The most massive tree she’d ever seen blocked the path before her. She looked up from her dirty feet and there it was, a wall of tree. Like early explorers mistaking the line of the horizon for an edge, the tree was so wide she couldn’t see its curve.

She circled it like the Earth around its sun, trying to count her steps, but always lost her place. First because Wren got nervous when he couldn’t see her after so long and flew to follow her, abandoning the spot where she’d know to stop. And then, after tying a loose bit of yarn to a twig and trying again, she failed to find it again.

Dasha quit trying to get the measure of the giant. The tree was big, that was all she knew. And she was supposed to climb it.

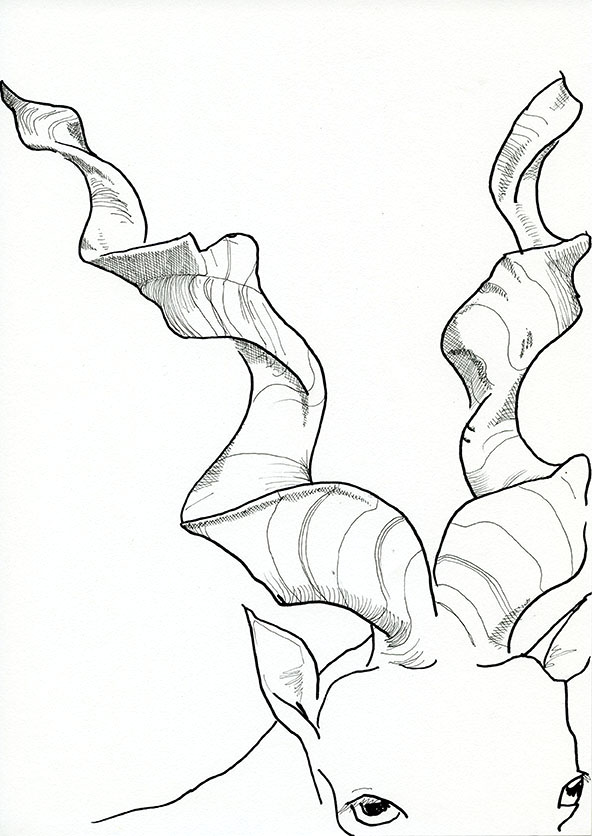

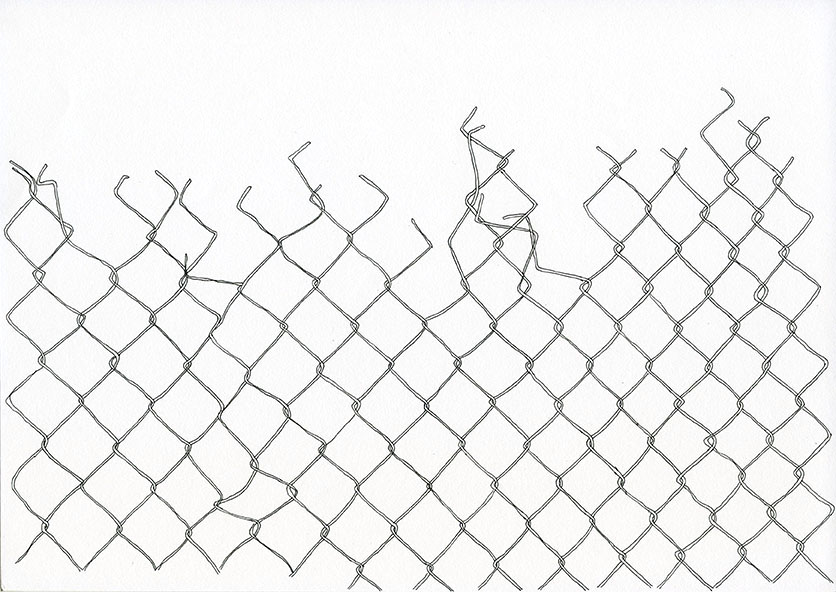

The pollen trail led to an unnatural barrier bisecting the forest. A great towering fence. The glowing particles drifted unimpeded through the metal twisting up out of the ground like vines.

Dasha approached the huge human-built fence and placed her palm to the metal weave.

The border, the wisent replied. The birds and snakes and seeds pay it no mind, but it keeps us divided. Contains the flightless folk on either side. Our families. Almost strangers now.

“What’s it doing here?” Dasha ran her hand along its smooth surface. “To keep you out. Or in.”

“Build a cage large enough and it almost seems like freedom,” Wren muttered and soared up over the fence.